The Proactive Ecology: resilient, circular and self-sufficient cities

by Maurizio Carta

[published in Monograph Research, n.2, november 2015]

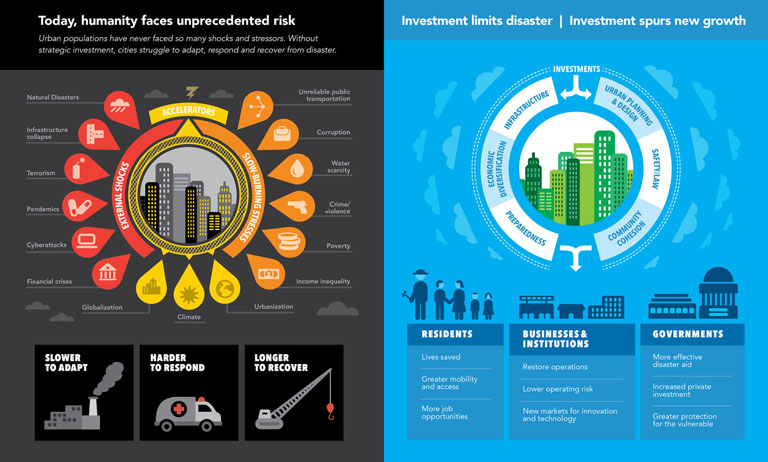

The Resilience Dividend

In the actual Anthropocene the world population is growing at a considerable rate, producing an impressive footprint on the Earth’s ecosystem. How long nature will be able to keep us with this is the main challenge for us? Climate change, water scarcity and rising resource prices show at an increasing rate that nature’s abilities are not inexhaustible. A resilience-oriented development, therefore, must act into a new urban metabolism in the urbanizing planet. When we plan and manage cities as organism with their own metabolisms it becomes clear that they are not separate entities. Cities use nature as their supplier of fuel, food, material resources and water, and nature also absorbs the waste generated by those cities. The urban population explosion has an ever-increasing influence on what nature is able to deliver. In order to set up an effective and action-oriented urban agenda, we have to redefine the way people lives, moves and works in cities. In 2013 The Rockefeller Foundation has launched the global challenge 100 Resilient Cities dedicated to helping cities around the world become more resilient to the physical, social and economic challenges that are a growing part of the 21st century. The initiative supports the adoption and incorporation of a view of resilience that includes not just the shocks – earthquakes, fires, floods, etc. – but also the stresses that weaken the fabric of a city on a day to day or cyclical basis. In a proactive vision, resilience is the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of structural crisis, chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience. Judith Rodin (2014), President of Rockefeller Foundation, call decision makers and development actors to improve the "resilience dividend", the collective profitability (material and immaterial) of a resilience-based development (Fig. 1). But how can a city realize the resilience dividend? It requires upfront investment both in terms of financing and resources. It requires innovation to solve for known vulnerabilities but also for variables unknown. And it takes partnerships with the private sector, both to uncover weaknesses within systems, but to also unleash the full range of financing for resilience projects and infrastructure. In turn, cities will see direct economic and social benefits. No doubt, new or upgraded infrastructure does require upfront investment (and city government leaders should be engaging the private sector to get it done). But that investment creates jobs today and in the long run it’s a money saver—it costs 50 percent more to rebuild in the wake of a disaster (environmental, economic or social) than to build the infrastructure to withstand the shock.

Resilience is becoming part of the criteria companies take into consideration when determining where to invest or locate operations. And in today’s global economy cities are competing for people as well as companies. Resilience should be a positive selling-point that cities volunteer to attract the best and the brightest, just as they might promote their livability scores, vibrant arts scene or new transportation investments. A resilience framework also creates a more diverse economy, a more different geography and a deeper innovation.

Contemporary cities, if we look them with new eyes, possess valuable "reserves of resilience," essential to plan and design them as vital organisms in evolution (Carta, 2014). These cells resilient to changes (fragments of the agricultural landscape, shreds of infrastructure, neighborhoods in functional recycling, drosscapes and brownfields) allow the city to take forms more elastic, less resistant to innovation and more adaptive. These reserves are used to enable resilience processes capable of handling a greater number of interacting problems, to engage the plurality of actors and diverse social archipelagos in decisions, and to implement forms of governance able to balance the competition between core and belt cities in an eco-systemic relation. And the cells of resilience from which to reactivate an urban metabolism more creative, intelligent and ecological focus in marginal areas excluded from the rhetoric of the turbo-development: suburbs in transition, industrial districts restructuring, port areas and railway infrastructures in recycling. Places – away from the driving centers of the urban model compulsive and consumer of land and resources – have been preserved community values, landscapes and heritage. Values that are precious resources for rethinking a city capable of absorbing the economic crisis, of managing social change and adapting to climate change, redesigning its structure, distributing its centers in reticular forms, resuming relations with the suburban, metropolitan and rural levels. Especially in the new eco-creative districts – more ecosofic – can restart a city that knows how to call into play its social, territorial and cultural capitals after being recovered from drug addiction drama from that we can call the “subprime urbanism”, that has anesthetized the ability to imagine, to plan, to root and to control.

In the new ecological and creative settlements – more resilient, dialogic and sensitive – the cycles of adaptation require a renewed elasticity and flexibility of functions, increased permeability of the spaces and fruitful adaptability of settlements. But these should not be addressed as a purely conceptual or spatial problems, but they must be put in relation with the social, economic and technological, today become structural parts of the urban planning, becoming themes / tools / rules for planning a new urban metabolism.

From Ecological Urbanism to Proactive Ecology

A major accountability is advisable when it comes to reckoning the scope and size of ecology applied to urban settlement systems, stretching beyond the urban territory. “The city, for all its importance, can no longer be thought of only as a physical artifact; instead, we must be aware of the dynamic relationships, both visible and invisible, that existing among the various domains of a larger terrain of urban as well as rural ecologies. Distinctions between rural and urban contingencies can lead to uncertainties and contradictions – calling for unconventional solutions This regional, holistic approach demonstrates the multi-scalar quality of ecological urbanism” (Mostafavi, 2010). According to this holistic approach, the territorial metabolism should be one of the key planning principles, contributing to reconnect agricultural, residential, industrial, natural, cultural and leisure systems with a view to collaborating and interacting within a mutual exchange of interests between beneficial situations or productive relationships able to influence the organization of space. San Diego is currently an example of how urban agriculture can be a political priority, a pivotal project for spatial, social and environmental regeneration in the disrepaired districts of the city, included in the planning rules, so as to provide the most disadvantaged social groups with accessibility, production and consumption of local agricultural products. In Istanbul the Collective and Collaborative Agency (KITO) set up a proposal for a post-urban development initiative that uses open-source, citizen-driven rural/urban regeneration to transform Toplu Konut İdaresi Başkanlığı complexes (Fig. 2). KITO works at different scales and levels of resilient action to retrofit spaces, equipment, services, and institutions. KITO’s collective interaction is facilitated via KITO’da, an online network that creates an alternative economy, assigning value to local actions and empowering people to make, give, share, and save energy, services, goods, knowledge, and skills. Instead of consuming the city, residents share in its production.

We need for a new "ethics of convergence" of interests will lead the new ecological sustainability, no longer as a frontier to be conquered for land-use planning – as was the case at the end of the last century – but as an operating challenge for a new urban metabolism, which requires to break down sustainability among the dimensions that characterize it (Ferrão and Fernández, 2013).

The political issue implying, first of all, the development of a culture of understanding and recognition of the other as a fundamental value of relationship, increasingly enriching the common interest through cross-fertilization between different experiences. Local identities are identified as active resources for the development of sociability and community within a sustainable political vision, as opposed to a culture of social polarization that tends to flatten the differences. There is in fact a direct relationship between the growth of the local society, democratic organizations and civic networks with strong bargaining skills in the context of globalization. The political dimension of sustainable development leads us to the implementation of "Lilliputian" strategies to interconnect local societies in order to increase their power to oppose the flattening laws of an exclusively financial globalization, regardless of knowledge and sociality: the global village shall go beyond the global market.

The environmental issue urges us to endeavour to work at territorial projects ensuring the ecological footprint reduction through urban patterns pursuing the reduction of mobility rate and, at the same time, products' (environmental and cultural, including food) improved quality and uniqueness, reactivation of agricultural activities with a view to multifunctionality and social factors such as the regeneration of the rural and urban land. And, to conclude with, the design of environmental systems and the conditions for their self-reproduction, as they are the main principle of urban settlement systems. Whether it is true, as claimed by David Owen (2009), that the city is – potentially –more sustainable from the ecological point of view than any other settlement forms, the road ahead will inevitably lead to strengthening urban ecological strategies not as mere norms, but as a political and operating projects, without ruling out the traditional tools of spatial planning. In Europe, following the launch of the new policy to tackle climate change, numerous experiments of "plans for urban climate" have been launched as a planning response to climate adaptation through a new metabolism.

Chris Reed and Nina-Marie Lister (2014) write that “the past two decades have witnessed a resurgence of ecological ideas and ecological thinking in discussion of urbanism, society, culture and design”. The concept of ecology has moved in favor of more contemporary understandings of dynamic systemic change and the related phenomena of adaptability, resilience, and flexibility. Increasingly these concepts of ecological thought are found useful as heuristics for decision-making generally and as models for cultural production broadly, and for design disciplines in particular. In Projective Ecologies the term “projective” is both important and suggestive: with it, the authors recognize the constructed nature of ecologists’ models for the physical and dynamic aspects of the natural world, as well as the limits of science in separating the observer from phenomena observed. So, the processes of which ecology and creativity speak are fundamental to the work of landscape architecture.

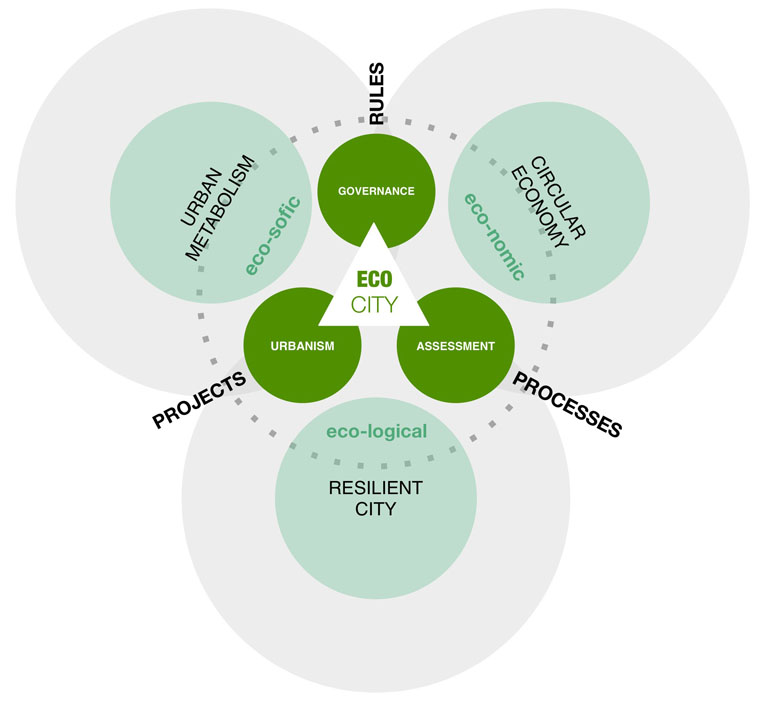

The Figure 3. shows the new approach of the proactive ecology in the new challenge for eco-city planning from sustainability to metabolism. Synthesis of the constant interaction between three components: governance, which produces the rules, urbanism that actives projects, and assessment, which guides the process. The interaction of these three components, therefore, creates the connection among “economic” components of the Circular Economy, “ecosofic” components of the Urban Metabolism and “ecological” components of the Resilient City.

The ecosofic dimension urges the system of public and private actors negotiating the development objectives to be as comprehensive as to ensure that the problems of the poorest social sectors are dealt with, as regards urbanism's collective dimension, enhancing its identification, handling and empowerment. The most interesting expressions of local self-sustainable development are based on the promotion, practices and objectives resulting from the local population's empowerment able to rebalance the relationship between powers (media, economic and political) thus ensuring that communication and participation are based on the legitimacy of the subjects, one of the key aspects of the communication ethics.

The economic dimension claims the need to overcome a vision of compliance with econometric parameters linked to a model of development model driven by integrated indicators highlighting the shift from mono-cultural concepts to complex socio-territorial economies ensuring the system's identity preservation, implementing exchange forms that are consistent with the increased assets value. Increasingly intangible economies, based on accessibility rather than ownership, encouraging social inclusiveness rather than segregation, well-being rather than wealth and efficiency rather than consumption are building an effective presence in the vision of the future (Jackson, 2009), requiring care and respect when it comes to the planning approach, that turns into a renewed co-opetition (cooperation + competition) and that reinforce the generative power of the sharing economy.

Finally, the ecological dimension provides infrastructure and landscape planning, as well as urbanism and, design with urban settlement patterns promoting the development of the four sustainability by identifying land use thresholds and proposals for the integrated settlements’ re-use and re-cycle. Redesigning urban tissues integrated with compatible productive structures requires public space reorganization according to the numerous communities that enliven cities today. We need a re-boot of the city generated by the redesign of the urban fabric in integration with the new micro and nano manufacturing, with makers and fablabs, able to generate the reorganization of urban space - increasingly shared - in relation to multiple communities that animate the city today. But above all, the sustainable territorial dimension needs creative urban planning and design: from local development and the gateway cities networks to creative cities, from the smart landscape to the bio-eco cities, where the interaction of many collective and multi-cultural intelligences, where several metabolic cycles and different energy powers produces new geographies (Ibanez and Katsikis, 2014).

We can see the explosion of a new generation of intelligent and ecological cities, districts and buildings: smart landscapes that improve social innovation, self-sufficient districts that feed the neighborhood, living buildings that respond and adapt to the conditions around them. In the proactive/ecological city buildings will function as a living organism in its own right, reacting to the local environment and engaging with the users within.

The responsibility for development metamorphosis and the commitment to re-imagining ecological urbanism from shared visions and addresses shall be implemented through a new roadmap, searching for methods and practices based on a few key points, that is the new ethic of responsibility for decision-makers and a new agenda for urbanists and planners.

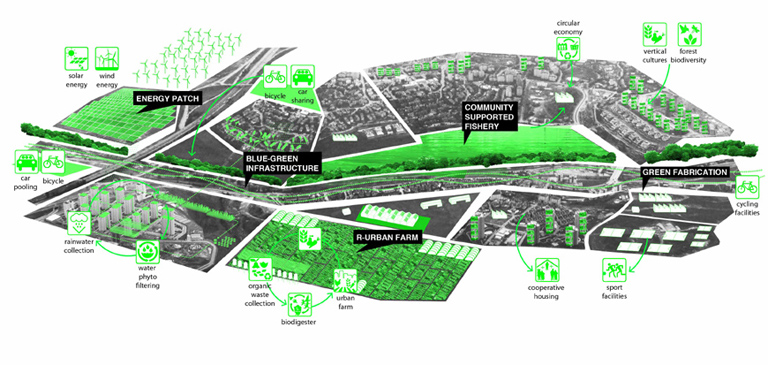

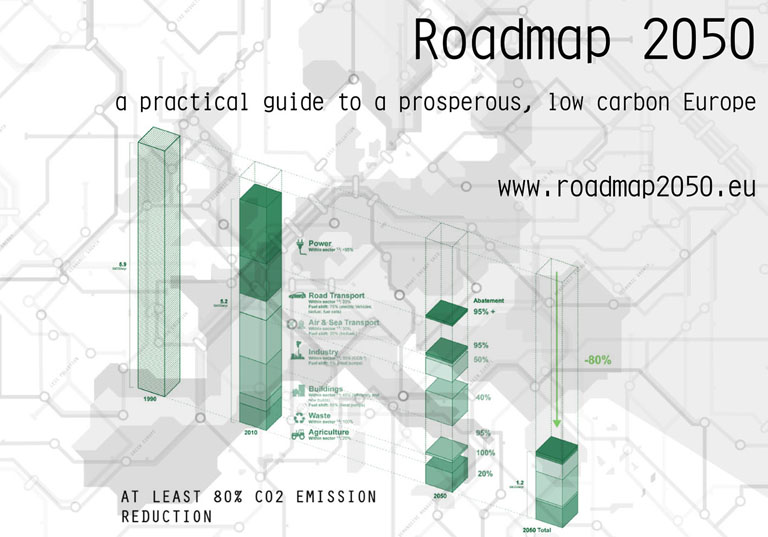

We must promote cities’ liveability, landscape quality, cohesion of inland areas, environmental sustainability and energy efficiency as a priority on the EU political and social agenda, particularly as regards Italy; rethinking more decisive measures for a new agreement generating greater innovation of processes, other than accelerating funds allocation or works. Land and landscape quality as well as environment and energy protection must be the benchmark of active policies for the implementation of new urban value. A new resilient-based agenda will be necessary for following in a creative way the EU Roadmap 2050 for a prosperous and low carbon Europe (Fig. 4).

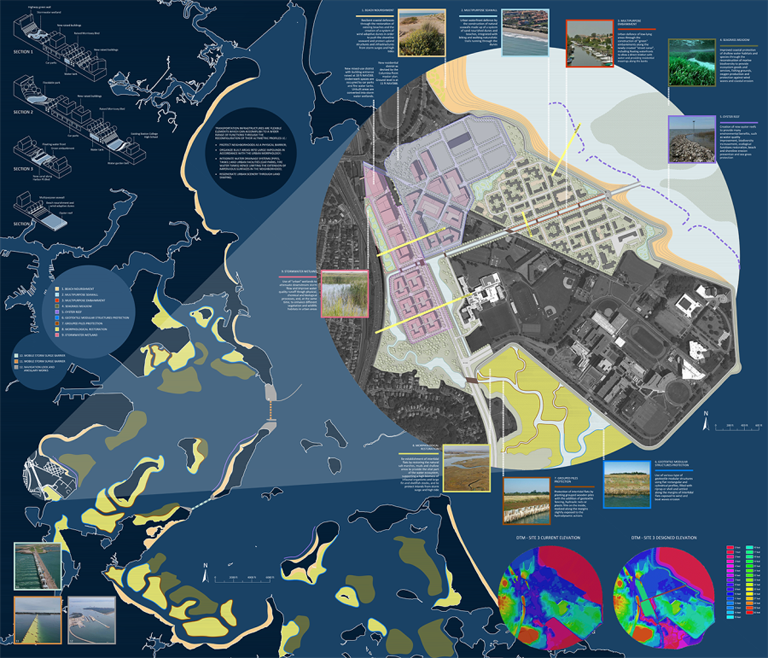

We must include new creative city sensibilities and paradigms within town planning in order to enhance urban talents, re-cycling urbanism paradigms in the practice of brownfield areas’ creative design, urban shrinkage paradigms as land project beyond consumption and the smartness ones, thus renewing the water-energy-waste cycles and managing digital and mobility networks in a sustainable way. Furthermore, the paradigm of post-carbon economy, driver of innovation and investment multiplier, of urban agriculture as activator of new metabolisms and finally of infrastructure retrofitting as adequate intervention method on inefficient cities need to be considered. From the edges of urban thinking – sometimes from its heresies – brand new topics should be the new heart of a "significant" urban project, once again. For example, the Boston Harbor Association, City of Boston, Boston Redevelopment Authority, and Boston Society of Architects have launched “Boston Living with Water”, an international call for design solutions envisioning a more resilient, more sustainable, and more beautiful Boston adapted for end-of-the-century climate conditions and rising sea levels. The competition seeks leading planners, designers, and thinkers to help the City of Boston and area businesses and residents develop and apply new concepts and strategies, including “Living with Water” design principles, to increase the City’s sustainability and climate change resiliency (Fig. 5).

And finally, we must renew urban designers and territorial planners' tools by merging them with ecological design, smart planning and open-source urbanism in a renewed cooperation aimed at implementing the metamorphosis by facing the challenge of creating new analysis and operational instruments if the traditional ones prove ineffective and obsolete.

References

Carta, M. (2014), Reimagining Urbanism. Creative, Intelligent and Green Cities for the Changing Times. Trento-Barcelona: ListLab.

Ferrão, P. and Fernández, J.E. (2013), Sustainable Urban Metabolism, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ibanez, D. and Katsikis, N. (2014), New Geographies 06 - Grounding Metabolism.. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Jackson, T. (2009), Prosperity without Growth. Economics for a Finite Planet. New York: Earthscan.

Mostafavi, M. and Doherty, G. eds (2010), Ecological Urbanism. Baden: Lars Müller Publishers.

Reed, C., Lister, N.-M. (2014), Projective Ecologies. Barcelona: Actar.

Rodin, J. (2014), The Resilience Dividend: Being Strong in a World Where Things Go Wrong. New York: PublicAffairs.